|

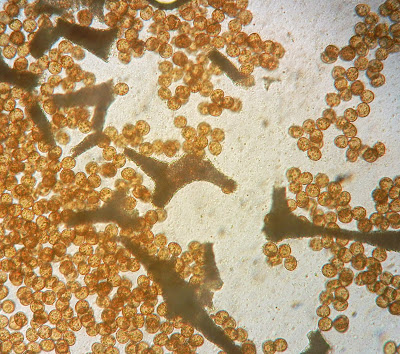

| Badhamia utricularis plasmodium engulfing Pleurotus populinus. |

I found my first fungicolous

myxomycete (a slime mold living on a fungus) two years ago in the height of the

Pleurotus populinus (spring oyster) season.

If I hadn’t been deep in the woods, I would probably have been able to see it

from a kilometer away, it was such an unearthly bright yellow-orange. Up close,

it was clearly an extensive slime mold plasmodium that was attempting to engulf

two separate clusters of oyster mushrooms that were well past their frying-pan

expiry date.

|

| Badhamia utricularis plasmodium Day 1 (top) & Day 2 (bottom) |

I could have left this

spectacle where it was, but I’d been wanting a new pet, so I took the whole kit

and caboodle home with me. I say “pet” because I’d read quite a bit about the

plasmodium of a particular slime mold—Physarum polycephalum—and had been keeping my eyes peeled, hoping to

find some that I could capture and tempt into solving mazes or planning efficient rail systems by baiting it with oatmeal as other people had been

doing. It sounded like fun. Cheap fun.

|

| The yellow plasmodium travelled on an off the mushrooms for several days. |

First, though, I was curious about whether or not

the plasmodium I’d found was actually consuming the oyster mushrooms I’d

found it on, or if it was simply passing over them. I took photographs over

several days and watched my myxo completely cover the Pleurotus, then

move off into a corner for a few hours (perhaps to relax and digest?), then

return to the quickly shrinking mushrooms and engulf them again. It repeated this

pattern for four days, and during this time the mushrooms shrank and shrank and

shrank. Unusually, there were no signs of the normal larvae that one finds gorging on

the tender flesh of the most edible Pleurotus species, the bane of

fungi-eating people everywhere, and I believe this was solely due to the

active presence of the plasmodium, which had either deterred the inevitable laying

of eggs by insects or had somehow made eggs that had been laid unviable.

|

| Plasmodium Day 4 (top) and Day 5 (bottom) |

An interesting thing about Physarum polycephalum,

which is studied in labs around the world, is that there are very few pictures

of mature sporangia—the structures that produce spores—on the internet. There

are even fewer examples of a progression from plasmodium to sporangia. Despite

this lack of sporangial evidence, there are many photographs of yellow

plasmodium on line that look just like mine, and a great many of these are

labeled as Physarum polycephalum. Some are engulfing mushrooms. Some of

these mushrooms are species of Pleurotus. Furthermore, in a 1987 paper,

Quentin D. Wheeler states that Pleurotus is “so often the substrate over

which this slime mold grows that the plasmodium is a field identification

“character” of the fungus itself (Lincoff 1981*).” Obviously, I had found my

first Physarum polycephalum. Or had I?

|

| The sporangia beginning to form. |

From early on, I was a tad disturbed by the colour

of my new “pet,” which seemed a little off, a little too orange-yellow compared

to the yellow to greenish-yellow it was supposed to be if it was really Physarum

polycephalum.

|

| Sporangia beginning to get their mature blueish grey colour. |

And then my plasmodium crawled away from the

flattened, liquefied remnants of the mushrooms it had been consuming and formed

sporangia that were not at all what they were supposed to be. In fact, what

they turned into was a big whack of Badhamia utricularis.

|

| Badhamia utricularis sporangia are brownish before drying to blue-grey. |

Surprisingly, this was not an anomaly. I found

another batch of mature B. utricularis in the winter that had apparently

been feeding on a Trametes before it, too, had formed sporangia. And

then, again, this past spring, I found new clusters of Pleurotus populinus

being eaten by, once again, B. utricularis at two different sites.

|

| B. utricularis sporangia are usually pendant, hanging in clusters by shrivelled yellowish strands. |

So I did a little more detective work and found a

most entertaining 1906 article written by a past president of the British

Mycological Society, Arthur Lister: “Notes on the Plasmodium of Badhamia utricularis and Brefeldia maxima.”

|

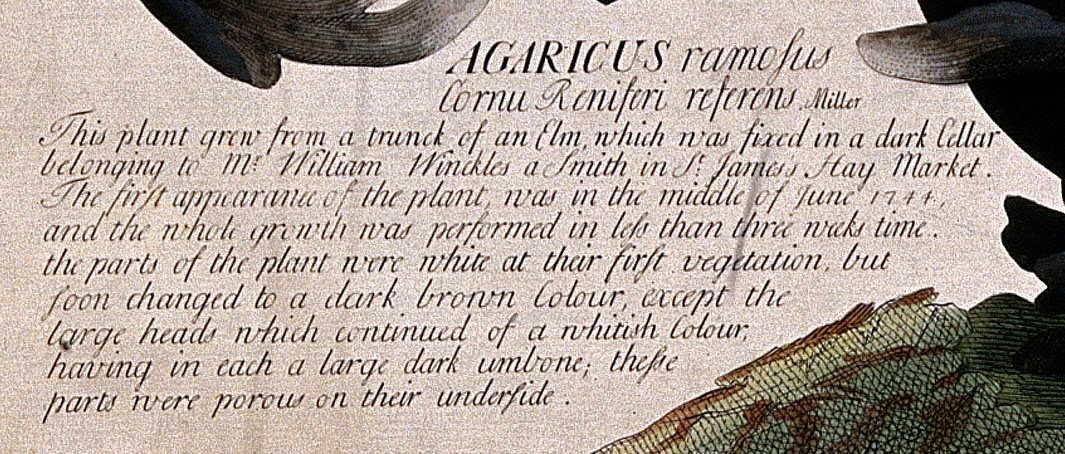

| Arthur Lister, who kept slime moulds as pets. |

Arthur Lister made his money as a wine merchant,

then retired so he could devote his time and energies to the study of botany, primarily

myxomycology, which allowed him time to observe and write notes about a pet B.

utricularis that he “kept in constant streaming movement on various types

of woody fungi for more than a year.” (Sometimes I wish I’d been a born in the

1800s. Male. To a family of means.) (Oh, yeah—with a daughter, Gulielma, who

would do all the gorgeous, detailed illustrations for my book: A Monograph

of the Mycetozoa (1894.))

|

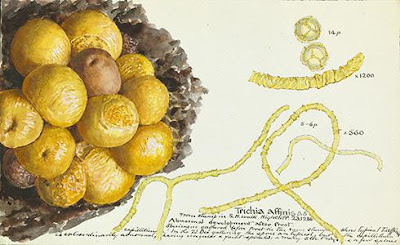

| Gulielma Lister and her amazing illustration of Trichia affinis. |

Lister found his Badhamia on a garden log

where it was consuming portions of an extensive patch of Coniophora puteana.

He captured some of it and kept it alive in specially constructed boxes,

allowing it to feed on thin species of Daedalea, Bjerkadera adusta,

Trametes versicolor, and, its particular favourite, Stereum hirsutum.

It also nibbled on Armillaria mellea and Suillus grevillei, and

partially consumed some Amanita rubescens. It was not thrilled, however, when

offered Hypholoma fasciculare. Though it politely fed briefly on this mushroom, it did not agree with it at all and the plasmodium, which was clearly ailing, did

not look itself again until it had been rejuvenated with a fresh piece of Stereum

hirsutum.

|

| I found this clutch in the winter. |

During Lister’s year of experimentation with this

plasmodium, numerous colonies made the change to sporangia. Others colonies,

however, though being given exactly the same conditions as the ones that had

matured, continued to stream and feed. Lister was unable to discover why some

chose to form sporangia while others did not. And nor have I.

|

| Weathered Badhamia utricularis |

This spring’s batch of plasmodium that I brought

home swarmed over the oyster mushrooms for several days until it had turned

them into a pool of mushroom-shaped muck and then it just went pfft.

Total dud. Though the plasmodium of B. utricularis is capable of forming

dormant sclerotium that can be revived when moistened, my last plasmodium

simply shriveled up and died.

|

| Badhamia utricularis spores & capillitium |

According to Lister’s notes, he never offered his

plasmodium pets any sort of Pleurotus. I wish he had so I could read his observations. In just two years, I’ve found it feeding on Pleurotus populinus three separate times, so obviously the organism takes some pleasure in eating it. I

believe other people have found B. utricularis on Pleurotus as well, other people who have jumped on a Physarum

polycephalus bandwagon for no other reason than their having found an

extensive yellow plasmodium engulfing a mushroom or

other fungus on a log. But I think it’s a fool’s game to try to name a plasmodium to

species without having the proof of sporangia. Pick it up, I say. Take it home. Enjoy the antics of your new “pet” until it chooses to reveal who it really is!

|

| A massive expanse of Fuligo septica plasmodium like this could be mistaken for either Physarum polycephalum or Badhamia utricularis. |

References & Resources:

Wired magazine's article about Physarum polycephalum & Tokyo rail system

Scientific American's article about Physarum polycephalum and mazes

Quentin D. Wheeler, A New

Species of Agathidium Associated with an "Epimycetic" Slime Mold

Plasmodium on Pleurotus Fungi (Coleoptera: Leiodidae-Myxomycetes:

Physarales-Basidiomycetes: Tricholomataceae). The

Coleopterists Bulletin Vol. 41, No. 4

(Dec., 1987), pp. 395-403

*Lincoff, G. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North

American Mushrooms, 1981

– In Lincoff’s defence, he does not say exactly what Wheeler says in the Audubon Guide. What he says in the

entry for Physarum polycephalum is that

they can be found “on dead wood and fleshy fungi,” and, under the entry for Pleurotus ostreatus: “It is sometimes

covered by the yellow early stage of a slime mold.”

This paper is “based on greenish yellow plasmodium collected on pilei of Pleurotus sapidus,” material that was cultured and proved to be P. polycephalum:

Howard, F.

L., The Life History of Physarum polycephalum. American

Journal of Botany Vol. 18, No. 2 (Feb., 1931), pp.

116-133